Shame arrives quietly. It rarely announces itself as shame; instead it appears as a tightening in the chest, a shrinking of the shoulders, a sudden desire to hide. It is the instinct to apologise before we’ve spoken, the sense that if someone truly saw us—fully, unedited—they might turn away.

Many people imagine shame as a flaw of character, something personal or secret. Yet shame is not born from who we are. It is born from who we learned we needed to be.

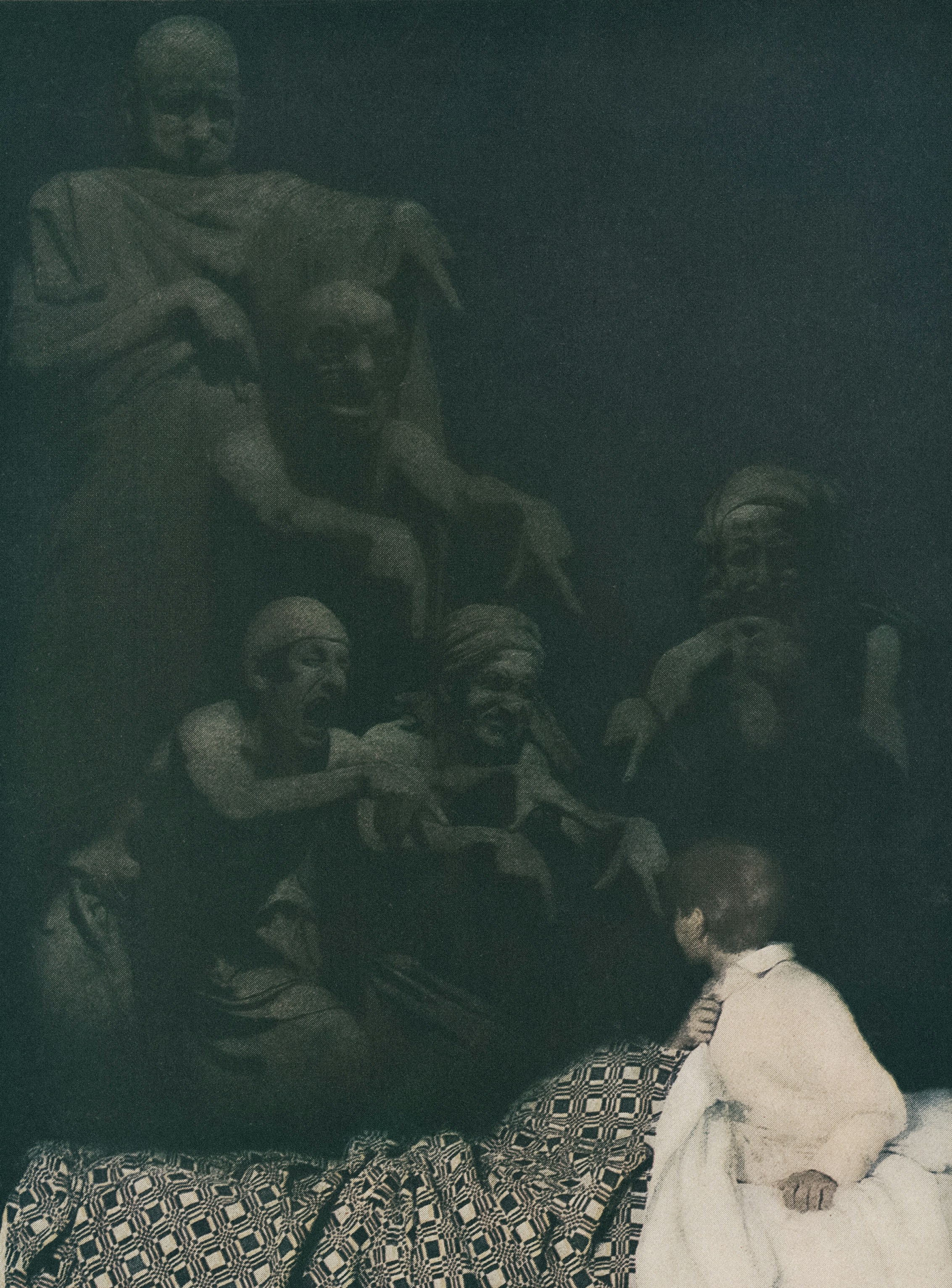

In childhood, the nervous system is porous. A harsh tone can feel like a storm; a moment of disapproval can register as a threat. The young child tries to make sense of the world through the only lens they have: “If the adults around me are unhappy, it must be something about me.” Shame becomes a kind of logic—an attempt to understand what is happening, and how to stay safe within it.

And so shame settles into the body long before we understand the word.

For some, it forms in the silences—when a caregiver is emotionally absent or inconsistent. For others, it forms in criticism, in chaos, in demands to perform or stay cheerful or grow up too quickly. Shame is often not about dramatic wounds; it is woven into the ordinary moments where the child feels unseen, misunderstood, or too much.

By adulthood, shame has become a familiar companion. It whispers from the edges of relationships. It shapes careers, intimacy, perfectionism, and the ways we protect ourselves. It tightens the breath. It fuels anxiety—not only fear of the world, but fear of ourselves. Addiction, too, grows from this soil: the attempt to soften what feels unbearable, or to escape the relentless hum of not enough.

But shame is not the truth of us. It is simply the echo of a younger self still waiting to be met.

The Inner Child and the Echo of Early Wounds

To speak of the inner child is not to indulge nostalgia or regression. It is to acknowledge that our emotional life did not begin at adulthood. The adult self is built on the architecture of experiences absorbed long ago. We are, in many ways, walking expressions of those early lessons—how we were allowed to feel, how we were responded to, what parts of us were welcomed or dismissed.

The inner child carries the memories the mind has forgotten but the body remembers: the way the stomach dropped when a parent was displeased, the loneliness of crying alone, the confusion of feeling wrong without knowing why. Shame lodged itself there, in that small, bewildered person who did not have the language to protest.

Healing is not about fixing that child. It is about allowing them to exist.

It is about meeting that younger self with the presence, curiosity, and care that they needed at the time. It is about letting them know—through tone, through breath, through kindness—that the old verdict of unworthiness was never theirs to hold.

What Healing Feels Like

Healing shame is not a single breakthrough or a triumphant declaration of self-love. It is quieter and slower. It often feels like sitting with discomfort rather than fleeing from it. It is noticing how quickly you want to apologise, and instead pausing. It is catching the familiar rush of “I’m getting this wrong,” and offering yourself a breath before the old script takes over.

It is beginning to hear the inner critic not as an enemy, but as a frightened child trying to keep you safe the only way they know how.

Healing also arrives in relationship—with a partner, a therapist, a friend—someone who meets your truth with gentleness rather than judgement. Shame dissolves in connection; it cannot survive being seen and treated with compassion.

But connection must begin within.

A Self-Help Practice: A Gentle Meeting with the Inner Child

Here is a simple, slow practice. Not a technique to “fix” you, but a way to reconnect with the part of you that learned shame long before you had the words.

Find a quiet moment. Sit somewhere comfortable. Place a hand on the centre of your chest. Let your breath fall naturally.

Imagine yourself at an age when you remember feeling small or uncertain. Do not force it—allow whatever age arises to be enough.

Stay with this image without correcting it, without making the child behave, without asking them to be brave. Simply notice them.

Then gently ask:

“What did you need that you didn’t receive?”

Not as an accusation. As a listening.

Perhaps they needed softness. Or steady presence. Or someone to explain that their feelings made sense. Perhaps they needed to be held without being told to stop crying. Perhaps they needed to be told that needing is not a flaw.

Do not rush to reassure them. Let the truth of their need be felt, even if only for a moment. This is the beginning of reparenting—not in grand gestures, but in the willingness to sit with what once felt unbearable.

If words come, offer them quietly:

“I’m here now.”

“You make sense.”

“You did nothing wrong.”

These are not affirmations to recite blindly. They are new experiences for the nervous system—experiences that slowly teach the body that safety and worthiness are possible.

The Deeper Truth

Shame is not a sign that you are broken. It is a sign that you adapted—beautifully, intelligently—to a world that once demanded you dim your light to survive.

The work of healing is not to become someone different.

It is to become someone more whole.

It is the slow remembrance that your tenderness was never a flaw, your needs were never shameful, and your younger self was always deserving of gentleness.

Healing from shame is ultimately a homecoming:

a return to the child within, and to the truth that they were never unworthy at all.